Open Data Is An Asset! New US Federal Guidance For Reaching Its Full Potential.

The recent Executive Order — Making Open and Machine Readable the New Default for Government Information and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) memorandum Open Data Policy — Managing Data as an Asset have brought much attention to efforts to promote the use of data by the US federal government. In fact, highlights of the US Federal Open Data Project are already impressive. Many agencies already provide their data in machine-readable formats through APIs, or at least downloadable data sets. However, I personally measure “highlights” in terms of the use of the data (not by the number of data sets accessible). And, many organizations already put this data to good uses in health, energy, education, safety, and finance. My recent blog, Open Data Isn’t Just For Governments Anymore, highlighted several examples of companies built on open data. Think Symcat, Healthgrades, oPower, or even Zillow which has been using public data for a while now. How many of you have “zillowed” your house, your neighbor’s house, or even a colleague’s house? Be honest. I have.

The recent Executive Order — Making Open and Machine Readable the New Default for Government Information and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) memorandum Open Data Policy — Managing Data as an Asset have brought much attention to efforts to promote the use of data by the US federal government. In fact, highlights of the US Federal Open Data Project are already impressive. Many agencies already provide their data in machine-readable formats through APIs, or at least downloadable data sets. However, I personally measure “highlights” in terms of the use of the data (not by the number of data sets accessible). And, many organizations already put this data to good uses in health, energy, education, safety, and finance. My recent blog, Open Data Isn’t Just For Governments Anymore, highlighted several examples of companies built on open data. Think Symcat, Healthgrades, oPower, or even Zillow which has been using public data for a while now. How many of you have “zillowed” your house, your neighbor’s house, or even a colleague’s house? Be honest. I have.

The new machine-readability by default and the directive on how to implement it reinforces and extends previous open data mandates with distinctly new implications for data initiatives. Here are some thoughts on the new policies:

An eye to future use is right – but use of what and by whom?

The guidance applies to all data – that which is destined to be open and that which will only be available internally: “Whether or not particular information can be made public, agencies can apply this framework to all information resources to promote efficiency and produce value.” And, both new and existing data: “The requirements… apply to all new information collection, creation and system development efforts as well as major modernization projects that update or redesign existing information systems.”

In theory, all data is fair game. But where to start brings up questions of cost, potential value, and privacy. On the question of cost versus value, the policy advocates that “Agencies should exercise judgment before publicly distributing data residing in an existing system by weighing the value of openness against the cost of making those data public.” OK, but how? Although complex, cost estimate can be made. But the “value of openness” is vague and undefined. What is the value of transparency? Or the economic value of the data? How do you estimate the economic value when we don’t know the potential uses? Did we know back in the 70s that weather data would spark a $510 million annual weather forecasting industry or a multi-billion dollar weather risk management industry? Did we know back in the 90s that GPS data would contribute $90 billion to the US economy in 2012? Likely not. While there is clearly potential value of open data, trying to assign a monetary value a priori is next to impossible.

Additional guidance on how to prioritize the datasets would have been useful: most-in-demand by developers? Requested via FOIA requests? Low hanging fruit? What would that be? And, is low hanging fruit even “worth it?”

The guidance is right-on in terms of the focus on “downstream processing and dissemination activities” –or simply put, the use of the data. Yet while the guidance refers to “consideration and consultation of key target audiences,” it seems considerably skewed toward the application developer. What about my mom? There is no mention of reaching out to the average citizen or the media – even with teaser visualizations. What about academics or think tanks who use the data to inform policy recommendations? The emphasis on machine-readability places a strong bias toward developers and the tech-savvy. While no audience is excluded, potential audiences are not included either. Guidance on how to identify potential audiences would be useful. At least example of how different audiences have used open data help to identify who to consider and consult – identify potential focus groups.

The matchmaking exercise goes in both directions. An information manager at a large public sector organization recently asked me how end-users found out about open data sources. This is a huge issue for open data programs. It’s a basic marketing fundamental: promotion. How do potential audiences find the data and how do agencies get the word out? A first step is through data inventories. The Memo stipulates that agencies create or update their data inventories. The goal is again to include all data – public, potentially public and not to be made public data – over time. A public listing – of just those data sets already published or potentially publishable – would be made available on Data.gov. But this remains an if-we-build-it-they-will-come marketing strategy. Promotion requires a strategy for outreach to potential audiences. Agencies, rev your marketing engines!

Metadata in the inventories helps identify data sets and their potential use and value. Metadata includes: origin, linked data, geographic location, time series continuations, data quality, and other relevant indices that allow the public to determine the fitness of the data source. An example is illustrative here. Metadata should include confidence levels – e.g., the agency is 70% confident in the quality of consumer spending trends or the agency is 95% confident of the quality of hospital success rates or of a particular medical procedure. In the first case, 70% is good enough for a targeted marketing campaign. In the latter case, a patient electing to undergo a medical procedure and selecting a hospital at which to get it done requires a high level of confidence.

While data inventories and metadata provide greater transparency into data availability, they don’t specifically help agencies to prioritize where to start, nor help in getting the word out about the availability of data. The Memo does establish a communication role – “communicating the strategic value” and “engaging entrepreneurs and innovators” – but falls short of a how-to with no examples provided. Are these outreach strategies understood among agencies?

Privacy protection and “mosaic effect” – a Sisyphean exercise or a potential shield, or both?

The Memo also clearly stipulates the need to protect privacy taking into account the “mosaic effect” – the scenario in which a single data set poses no privacy risk but aggregation of multiple data sets could reveal personally identifiable information. Agencies must consider the effect not only of existing open data but also data to be published in the future. How onerous is that analysis? Recognizing the complexity of the effort, the Memo offers data.gov expertise to help assess potential privacy risks. Can they see into the future? The intent is good but is the requirement too restrictive? Given the potential reach of the “mosaic effect,” could it become a shield behind which any reluctant agencies could hide?

The Memo also clearly stipulates the need to protect privacy taking into account the “mosaic effect” – the scenario in which a single data set poses no privacy risk but aggregation of multiple data sets could reveal personally identifiable information. Agencies must consider the effect not only of existing open data but also data to be published in the future. How onerous is that analysis? Recognizing the complexity of the effort, the Memo offers data.gov expertise to help assess potential privacy risks. Can they see into the future? The intent is good but is the requirement too restrictive? Given the potential reach of the “mosaic effect,” could it become a shield behind which any reluctant agencies could hide?

Incorporating open data into core agency process is good – but how do you measure success?

The Memo rightly specifies that the new open data policy must be incorporated into existing information resource management and into the agencies strategic priority goals. Clearly, we don’t want open data initiatives to exist outside of other information processes – which are where some have resided to date. That move to internalize open data gets agencies closer to defining their success, and creating incentives to get there. Success can’t be measured in data sets and downloads – or even calls to the API. Agencies must define their success by the use of the data and the business outcome – market development and growth like the weather industry, job creation, cost avoidance through crowd-sourced app development, cost savings from operational innovation and policy review, or even in some cases revenue generation. Other than the glory and satisfaction of complying with an Executive Order what is the incentive structure here? How do these new open data measures advance agencies in their existing strategies and toward their existing goals?

Information governance as a working group – not a new Chief

I was excited to see the creation of an inter-agency working group in the Memo. The data governance question is a big issue for both the public and the private sector. My Too Many Chiefs? blog advocates the working group approach rather than a new Chief Data Officer position – a new local government phenomenon. We don’t need a federal CDO. But we do need to coordinate and share best practices across agencies – and also within agencies. The working group model should be applied intra-agency as well to bring together both those who collect the data, those who provide the tools to manage the data (IT) and those who use the data (business intelligence users, citizen engagement specialists, “product” management).

Infrastructure and enterprise architecture – machine readable also means robust!

Another question I had but which I will have to confer with others to fully address is around the technology. What is the recommended infrastructure for information systems? While the guidance refers to Common Approaches to Federal Enterprise Architecture, does that mean cloud first? Is there a provision for shared services? There is clearly a reference to agile in the requirement that the choice of infrastructure take into account potential changes in internal and external needs “including potential uses not accounted for in the original design.” Infrastructure is critical, and machine access can challenge even the best architected system. Apparently when Transport for London launched its API, the first apps to go live crashed the system. Overhead signs in the Tube went down. I have yet to confirm this but true or not the scenario must be part of the planning process for any agency launching an API. But I’ll look into this further with my EA colleagues and get back to you.

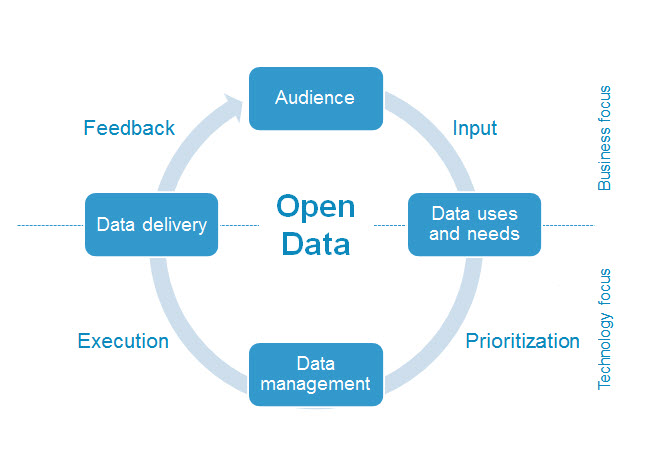

While supporting existing open data mandates, the new Executive Order and OMB Memorandum are extremely positive steps in encouraging the use of public data as fuel for innovation. The following graphic provides a simple methodology for approaching the task. In short, determine potential audience through promotion of open data, with input from them identify potential uses, determine appropriate data and eligibility for publication – which also serves as a means of prioritizing data publication, manage and deliver the data, solicit feedback, revise or repeat.

I look forward to hearing more about and helping with the implementation of the new Executive Order and its accompanying OMB Memo. And can’t wait to see what the private sector will do with their new and facilitated access!