Smarter Cities Rio: From Blueprint To Proof Point For Cities Large And Small

This past week I attended IBM’s Smarter City Summit in Rio de Janeiro, the fourth in a series of global events highlighting the opportunities for cities to improve their systems — and themselves as a “system of systems.” This event felt different from the previous summit I had attended in Shanghai. Obvious political and cultural differences aside (not to dismiss them, as they were significant), the big difference I observed here was that the sessions were more real. And I don’t mean that as a slight on the Shanghai event. Rather, in Shanghai, the focus was on moving from vision to execution– creating the blueprints for smart cities. In Rio, we had moved from blueprints to proof points. (Yes, you can quote that . . . it is mine.) Mayors from cities across Latin America and some from even farther came to share their experiences.

This past week I attended IBM’s Smarter City Summit in Rio de Janeiro, the fourth in a series of global events highlighting the opportunities for cities to improve their systems — and themselves as a “system of systems.” This event felt different from the previous summit I had attended in Shanghai. Obvious political and cultural differences aside (not to dismiss them, as they were significant), the big difference I observed here was that the sessions were more real. And I don’t mean that as a slight on the Shanghai event. Rather, in Shanghai, the focus was on moving from vision to execution– creating the blueprints for smart cities. In Rio, we had moved from blueprints to proof points. (Yes, you can quote that . . . it is mine.) Mayors from cities across Latin America and some from even farther came to share their experiences.

For example, representatives from Singapore, London, and Lima shared the challenges and successes of implementing new transportation initiatives. Singapore deals with a growing population on an island, meaning there is no opportunity for sprawl and therefore “private cars are no longer an option.” As a result, the Land Transport Authority (LTA) has a goal that 70% of all circulation or “daily trips” will be by public transport. It is almost there. The strategy was twofold. LTA makes it really expensive to drive a private car: cars are taxed at 120% and the ownership license distributed via auction was $60,000 in the latest round. Not to mention the congestion-based tolling system when you actually do use your car. On the other hand, LTA has improved the experience of public transportation through an integrated transport system, predictive arrival times, and notification of arrivals, among other things.

London’s congestion pricing provided another example of progress: car use has been reduced 70% in central London. Transport f or London (TFL) — which I blogged about last year — recently launched Autopay to ease the pain of the scheme. Cameras register use as they pass into the tolling zone of the city center and drivers are billed at the end of the month; a variety of payment mechanisms is available.

or London (TFL) — which I blogged about last year — recently launched Autopay to ease the pain of the scheme. Cameras register use as they pass into the tolling zone of the city center and drivers are billed at the end of the month; a variety of payment mechanisms is available.

In other breakouts, representatives of the City of Madrid discussed their Centro Integrado de Seguridad y Emergencias de Madrid, and Rio de Janeiro showed off its new Centro de Operações Prefeitura Do Rio, both for coordinated emergency management. The Rio Operations Center integrates information and processes from across 30 different city departments for a holistic view of the city 24/7.

Smart Cities Come in All Sizes

But the story told was not only about mega-cities — the big cities we hear most about. Mayor Johnny Araya Monge of San Jose, Costa Rica — a city of 350,000 inhabitants with a metro area population of 1.7 million — asserted that “countries should have networks of mid-sized cities to avoid the emergence of mega-cities.” He then shared his initiatives to revitalize San Jose’s city center including the creation of an urban forest, reductions in crime through video surveillance, and extensive e-government services such as online tax payments. On the other end of the size spectrum was Tigre, Argentina, a city of around 30,000 in the Buenos Aires Province. Tigre Mayor Sergio Massa outlined his initiatives and the benefits his constituents have already seen. Security cameras and improved public safety reduced car theft such that car owners saw a 40% fall in car insurance premiums. According to Massa, mayors “want our cities to play a role in urban planning. We want to make our cities thought leaders.” Even smaller cities can play that role.

In a keynote on the second day of the event, the president of the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Luciano Coutinho, explicitly lauded the opportunity for and the role of mid-tiered cities.

- Mid-tiered cities can avoid the problems already faced by mega-cities. Leveraging the tools available by implementing new, “smarter” urban policies can create more sustainable city policies and preempt some of the urban issues associated with dense population.

- Initiatives in mid-tier cities will also attract investment, create jobs, and subsequently eliminate the incentives for moving from these cities to the major urban centers. A positive environment in smaller cities stems the flow of migration to the mega-cities.

According to recent McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) research, Latin America already has about 80% of its population living in cites, growing to about 85% by 2025. At a country level, Brazil is already 87% urban, Chile 89% urban, and Argentina 92% urban. Basically, Latin America is already urbanized, similar to the US and Western Europe and in contrast to China, which has 47% of its population in cities, and India, which has only 30%.

According to recent McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) research, Latin America already has about 80% of its population living in cites, growing to about 85% by 2025. At a country level, Brazil is already 87% urban, Chile 89% urban, and Argentina 92% urban. Basically, Latin America is already urbanized, similar to the US and Western Europe and in contrast to China, which has 47% of its population in cities, and India, which has only 30%.

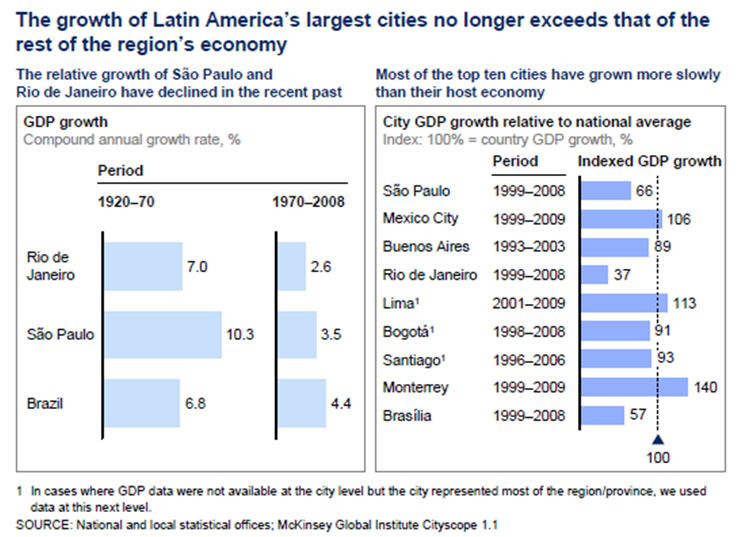

But while Latin America’s largest cities together contribute more than 60 percent of GDP today — with the top 10 cities contributing half of that output — the growth rates in Brazil's São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro have dropped from above to below the national averages in these two economies (see chart). The same is true for other countries. The mega-cities don’t always drive growth, and MGI expects this trend to continue. It’s the dynamism of the mid-tier cities that drives growth.

What does this mean from a “smart city” perspective? What’s the lesson for tech vendors?

- Don’t forget the mega-cities, which need help to reform both their physical and digital environments and to remain competitive.

- But don’t neglect the smaller, mid-tier cities, which can learn from their bigger siblings to avoid potential pitfalls of urbanization and growth. They are the cities eager to attract investment and create jobs in order to keep their citizens and continue their economic growth.

In Latin America, cities of all sizes are addressing their urban challenges. And information and communication technology is an enabler.