Is Facebook Listening? (And So What If They Are.)

From time to time, an anecdote comes across our desks that, as researchers, we find hard to leave alone. A few months ago, one of these opportunities appeared, and we thought it might be interesting to lift the hood, and show you how we dig into tough research hypotheses and decide if and when to write about them. Here's what happened.

******************

Over a period of a few days this winter, we heard from one colleague, then another – 20 in all — that conversations they'd had IRL ("in real life") seemingly resulted in ads and sponsored posts in Facebook. Given the state of "surveillance marketing," we weren't that surprised, until we read Facebook's T&Cs. There, the company explicitly stated that it wouldn't use data collected from a user's microphone for ad targeting. That's when we got curious.

First, we looked to the obvious: had our colleagues searched for the advertised item after having had the conversation? Had they checked into the same place as their friend, at the same time? Were they on the same network — and thus sharing an IP address — as someone who'd searched for the product or service? We rounded up the answers to these questions, and determined that "interest-by-proxy" was an unlikely cause.

At the same time, we were thinking about the technical capabilities required to 1) listen to an ambient conversation on a mobile device; 2) identify specific terms or phrases; and 3) funnel those interests and propensities to audiences for ad targeting. This is technically very challenging. Natural language processing is hard in the best of circumstances; layer on data limitations and background noise, and it becomes the stuff of science fiction. So we ran a few tests to see whether the Facebook app functioned differently when it had access to the microphone than when it was blocked. In our first run, we struck out — the app didn't seem to send or process more data if it had mic access.

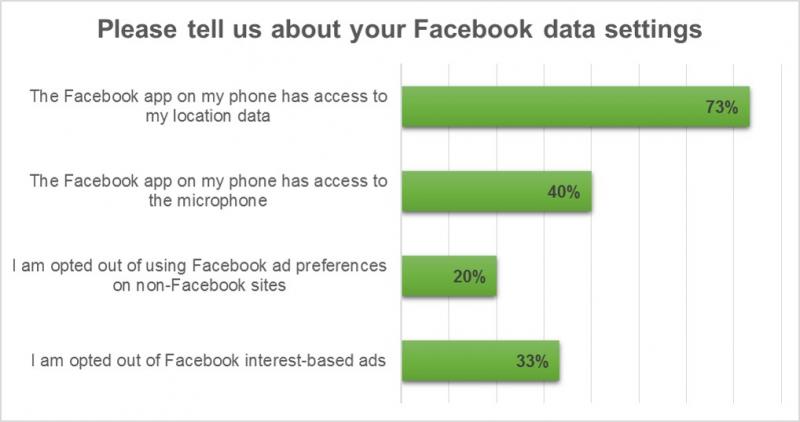

Then, we surveyed the individuals who'd reported the experiences to calibrate the "anecdata." We collected qual and quant data in a structured format, looking for details like the context of the incident; whether the user was FB friends with the person they were chatting with (nearly a third were not!); and the user’s FB permission settings.

While there are some interesting findings, we haven’t been able to prove our hypothesis yet. But here’s why we’re continuing our study:

- Consumers aren’t ready for the wall between the online & offline world to crumble. Of course, in some cases, they are happy for the brands they trust to triangulate data across digital and physical channels. But when people feel like they haven’t been given a meaningful choice about cross-device or location based targeting, it affects their trust in a brand. That effect would be amplified if they felt their conversations – which they expect to be private – were being monitored for marketing and advertising purposes.

- If Facebook has upped the ante, all advertising will suffer. Already, 24% of US online adults have installed an ad blocker. Typically, this is the result of a few “creepy” or annoying experiences, but the net effect is that the entire online advertising ecosystem – from publishers to networks to advertisers – suffers. If Facebook is targeting online ads based on physical conversations, the number of consumers that opt-out of advertising via ad-blocking, tracker tracking, and privacy tools will skyrocket.

- If consumer protections kick in, they'll damage Facebook’s advertising platform. We think it’s unlikely that Facebook would be testing mic-based ad targeting anywhere outside of the US. But European regulators will be hypervigilant if they catch wind that this could be happening – and they’ll target advertisers as much as they’ll target Facebook if they perceive a privacy infraction. US regulators won’t loll about, either – they’ve already come down hard on SmartTV manufacturers that used passive listening to sell targeted ads, and Facebook is a far more fertile target.

We’re the first to admit – we can’t be 100% certain how or when Facebook is capturing ambient data from smartphones. But we also know that the digital ad ecosystem can only withstand a certain number of privacy violations before it falls apart. So, whether you’re an advertiser, an agency, or an adtech firm – if you think you know what’s going on, please send us a note or a Tweet*. And watch this space over the next few months as we continue our investigation.

*As thanks, we'll send you a copy of "Level Up Your Privacy Game," a guide we put together for our Forrester peers. And, as always, when we publish our findings, we’ll provide attribution in the final report.

(This post was produced in collaboration with Christopher Sherman, Christopher McClean, and Carrie Johnson)